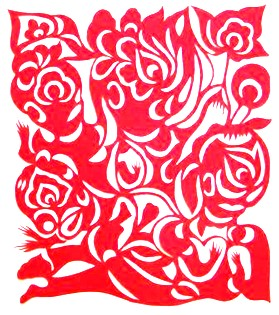

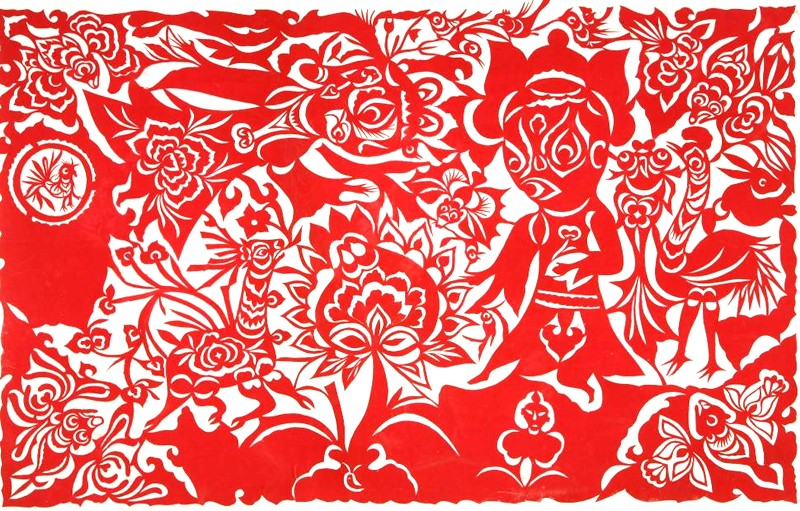

The family rules and the village covenants constituted two seriously prescriptive forms of folk ritual culture. For the scholars, who were expected to join the scholarly class, schooling was the main way to receive the ritual system, while for the non-student class of women and manual laborers, the family rules and village covenants became the direct rules governing their thinking and behavior. The Confucian concept of the unity of the family and the state was often reflected in the family rules, and the moral ethics of loyalty, filial piety, faith, and righteousness were carried out in the daily lives of family members. We often see that the richer and more prosperous the family, the more stringent such family rules were, and this was the model responsibility they took on in civil life. Gao Fenglian's paper-cutting work, Sheep Herding (Figure 3), describes this kind of discipline: “When I was a child, it was fashionable for girls to go to school in the village. My father would not let me go to school, saying that it was a shame for girls to go to school. I followed my brother in carrying the sheep sweeper (behind the sheep), and I used to take my grandmother’s small scissors secretly in those days, and when the sheep were grazing smoothly in the mountains, I searched for some leaves, hemp leaves, mulberry leaves to cut blindly some flowers, birds, fish and people and horses (people riding horses) with my scissors.”

It is because the family of Gao Fenglian's mother (娘家in chinese) was once a high-class family, “grandfather’s grandfather wore boots and a top (an official),” “the family (the place of residence) had a stone courtyard, a stone road, a stone dragon gate, and a pair of stone lions on both sides of the dragon gate, which were imposing and powerful.” As a result, even her father's generation, which had slipped into decay and poverty, followed stringent familial family rules, and followed Confucian culture’s rules for men and women. Her marriage was arranged by her father, without any resistance, to a cousin’s family, who was even poorer than hers.

The family rules, that is, as the lowest unit of structure to accomplish the ceremonial system of brainwashing in the civic group. And as a bridge between the state and the individual in the education of ideas and ideologies, the village covenant played an important role. “The township covenant sprang from the reading of the law in the Zhou dynasty, was formed in the Song dynasty by the Lüs, began to be promoted by the government in the Ming dynasty, and was popularised in the Qing dynasty.”[4] The village covenant was a way of enforcing rituals in a more extended and institutionalized way, based on the indoctrination of the individual by the family, and reflected a shift in Confucian culture, which was supported by the regime, from a “religion of music” to a “religion of punishment.” The judge in the covenant is a well-read, elderly man who is guaranteed to have a deep understanding of Confucianism, and who assumes the role of the head of a larger family, with unshakable authority. The final development of the village covenant, with a weakening of the responsibility for indoctrination and a gradual increase in the administrative function at the grassroots level, is also evidence that the means of indoctrination of the people by the cultural ideology at the top was inherently coercive in character.

Both the family rules and the village covenant can be seen as a form of administrative edification, but the broader act of indoctrination is the pervasive infiltration of folk customs into the daily lives of the people in terms of food, clothing, housing, and transport. “Folklore refers to the culture of life created, enjoyed, and passed on by the general public of a country or nation. Originating from the needs of human social groups, folklore is constantly forming, expanding, and evolving in a particular nation, era, and region.” [5] Ying Shao’s General Theory of Customs contains much of the importance attached by upper culture to folk customs as a matter of national stability; for example, it records the Southern Song scholar Lou Yao as saying, “The vitality of the state is all in the customs, and the essence of customs is really a discipline.” Thus, the infiltration of Confucian cultural thought into folk customs was a transformation for a unified idea of “transforming social traditions.”

The progress of production technology was certainly an intrinsic motivation for the change in human perceptions, which set the standard of behavior of folk culture in favor of labor, but this standard did not contradict the need of the people to pray to ghosts and gods. Labour was the only means by which they could change their lives and increase their self-affirmation while praying to the gods and ancestors allowed them to find a home for their spirits. It can also be said that the primitive concept of worship in folk cultural consciousness is on the one hand diminished by the growing self-confidence of mankind, and on the other hand supplemented by new human needs, all of which constitute the law of folk cultural flux and the general law of self-renewal of folk culture. This law is also governed by the influence of the dominant culture of society, i.e., by the will of society as a whole, as determined by the culture of the hierarchy, which has a more important role in guiding the evolution of folk culture, as a result of the choices made by the hierarchy.

Edification in rites and music and Shintoism: the rules from the upper culture

The so-called “culture of the upper classes” generally refers to the cultural content that is separate from the grassroots production and has a certain “specialized” ideology, which often corresponds to the ruling class, the scholars, and the literati, forming the main culture of a society or the “elite culture.” From the time when the rational philosophies of the pre-Qin scholars were used to experiment with social norms, Chinese upper-class culture grew out of the original culture and from then on distanced itself from the original culture, which still extended at the grass-roots level among the people, and soared to an independent level of cultural consciousness with a humanist ideology, whose creators and users generally had a sense of responsibility to cultivate themselves, to rule the country and to pacify the world in order to achieve the cultural will to maintain national unity. Thus, the rational consciousness and ritual requirements of the upper culture constituted the external impetus for the evolution of folk cultural concepts.

The close interaction between the upper and lower cultures in China allowed them to interpenetrate within their own systems, and although they were able to develop separately, the exemplary nature and power structure established by the upper culture facilitated the creation of strict internal regulations within folk culture, and such regulations were the most important part of the generation of folk cultural ideas. Moreover, changes in the ruling class of society brought about changes in the cultural orientation of the core upper class, as well as changes in the conception of folk culture, and what remained unchanged was the constant use and transformation of the normative nature of culture in response to different institutions. This is where the rulers of any stratum of society seek to establish an ethical and moral code that harmonizes social demands and stabilizes social order - a cultural regulatory mechanism for social harmony. The on-demand flux molded by folk culture's internal processes, which is based on the natural “biology” of the demand, and the uncontrolled expansion of its desires, are bound to cause a certain degree of damage to the complex structure of the human social organization, and therefore the regulation of it by the higher culture is an inevitable consequence. We say “use” and “transformation” of the law because “ritual and music” and “Shinto establishment” are the two methods by which the higher culture accomplished “culture” for the people of ancient China.[2]

Rites and music for edification

The connotation of “rites” in ancient Chinese culture includes the principles and norms of governance of all things, covering various fields such as politics, ideology, academics, institutions, rituals, and customs; “music” includes musical composition, which is a humanistic art form combining “poetry,” “song” and “dance.” Although “ritual and music” was developed under Confucianism as a way of educating and regulating the people through ritual and music, we can already see the beginnings of a ritual system in the clan period. The earliest “rites” was based on the philosophical idea of obedience to nature and the unity of man with nature, which was determined by the low productivity of early mankind. Only by integrating human growth and development into the orbit of nature, and by working and living based on the knowledge and understanding of the laws of nature, could we achieve sustainable development for individuals and tribes. In addition, the war and strife between the clans and tribes also led the clan leaders to gradually understand the concept of “cultivating virtue to teach, and the world will return.” From the Records of the Five Emperors (Shihchi: Biographies of Five Emperors), it is recorded that the Yellow Emperor “cultivated virtue and revitalized the army, ruled the five qi and the five kinds of art, fostered all the people, and measured the four directions,” it can be seen that the “successful” political leaders of the ancient times already knew that the pursuit of heaven and earth (opportune time and geographic advantage) alone could not guarantee the sustainable development of the tribes. From the demonstration of self-morality by the main body to the imitation of the members of the tribe, social norms of behavior were gradually established, up to Yao, Shun, and Yu, when the establishment of the Zen transfer system can be taken as the best interpretation of the ritual norms.

The term “edification” is attested to by scholars: “The term edification first appeared during the Warring States period, but the practice of edification emerged as early as the time of Yao and Shun,” and “Yao and Shun were the ones who were good at edifying the world (Xunzi)”. “The term ‘edification’ also appears more frequently in Xunzi, e.g., ‘On rites and music, correcting one’s conduct, extensive edification, and beautiful customs;’ from the above it can be seen that the original meaning of edification is to transform the people into good by the teaching of ritual and music, and its significance is to enable the people to move closer to goodness and far from sin without being aware of it and to have the effect of changing customs.”[3]

The idea of effective social organization and governance has been accumulated and King Tang of Shang, King Wen of Zhou, and King Wu of Zhou, and then by the Duke of Zhou, who composed the Rites of Zhou and made the rites and music to promote cultural governance and education throughout the country. The system of rites and music was the result of a leap from spontaneous to conscious thinking, which was also the result of a productive way of life and long-term political practice.

The Confucian idea of ritual and music was the result of reflection after the Spring and Autumn wars and the collapse of ritual and music. The ideological system founded by Confucius, Mencius, and Xunzi, as the main ideology of Chinese upper-class culture, used music as an important basis for social and moral norms, advocated universal education with “instruction knows no class distinction,” and the establishment and cultivation of saints and gentlemen. All this determined the basic way in which the Chinese people were taught to think and behave, and the direction and way in which folk culture changed on an agrarian basis.

This is why the rulers of the upper echelons of Chinese power and the cultural masters of the upper echelons, who had a philosophy of cultivation and governance, always attached importance to and paid attention to folk culture, as the Eastern Han scholar Ying Shao states in his Preface to the General Principles of Custom: “The most important thing for the government is to identify and correct the customs,” emphasizing the important role of the ruling class in intervening in folk culture.

The idea of respect for heaven in Confucianism is a continuation of the original culture’s worship of heaven and earth. Confucianism, as a superior culture, first emphasized the unity of heaven and man and the conformity to heaven and man, which echoed the concept of the passage of heaven in folk culture, objectively conforming to the productive life of the lower classes and respecting the laws of nature to ensure the well-being of folk life, winning resonance with the position of the folk people.

On this basis, the ruling class presided over the state rituals to worship heaven and earth, mountains and rivers, all with the content of “worshipping heaven” and “relatives (protecting People)” to pray for fair winds and rain and to ensure the well-being of the people, catering to the ideal of survival of the people. Thereby, the mountains and rivers become an apotheosis of power, and the title “Son of Heaven” further clarified the important position of the power controller in folk beliefs and worship, thus leading the worship of heaven and earth in folk cultural concepts to power worship centered on the “Son of Heaven,” and the rituals of heaven and earth also The rituals of heaven and earth completed the process of “ecological” indoctrination of the people. This led to the creation of rules for compliance with the centers of power, leading the folk to respect nature and their own self-confidence, to respect power, and to follow the path designed by this power class to obtain “blessings.”

Chinese folk culture is devoted to the completeness, and stories or legends rarely have “tragedies,” but often have “happy” endings. The story of Chen Shimei, who was beheaded in the Guillotine Case, was more a testament to the harshness of the official law and the ruling class’s self-imposed fairness in enforcing the law, although it was in line with the folk’s desire to promote good and punish evil. The tale of Gao Fenglian’s scissors is more in accordance with people’s acceptance of Confucianism’s “natural virtue.” Even when dealing with people who had betrayed their trust and righteousness, they would report with good hopes, believing that education and probation would lead to their conversion to righteousness. On the other hand, it is also possible to illustrate the implementation of the Confucian idea of “family and state as one” in folk culture: firstly, it extends from the code of conduct in family life to the code of conduct between people in society, forming a top-down social moral code, with “benevolence and love” as the central moral standard. The second is the emphasis on personal cultivation, as the saying goes: “Cultivating one’s moral character leads to a harmonious family, a harmonious family leads to a well-governed state, and a well-governed state leads to an ideal universe.” For the individual to be able to “level the world,” the harmony of the family, the smallest unit of society, must be ensured. Therefore, for those who have risen to the rank of the civil servant, their code of conduct has a bearing on the stability and harmony of the state. Confucianism’s “benevolence” was obviously more deeply rooted among the people than among the officials and gentry.

The above works are just a drop in the ocean of Gao Fenglian’s vast collection of paper cuttings about folk legends and stories, which have been passed on from generation to generation, as the young girl inherits from her mother the skills of paper cutting, as well as a ritualistic approach and the continuous transmission of the cultural spirit of a community. So, it is this function of ritual and edification that is the most fixed element in the flux of Chinese folk culture.

A combination of naturalism and moral righteousness

The phrase “the divine way of teaching” is taken from the Tuan Chuan of the Zhou Yi: Tuan (The book of changes: Commentary on the Decision): “Observe the divine way of the heavens, and the four seasons do not fail. The sages set up teachings with the divine way, and the world is convinced.” In the long history of ancient Chinese society, it was highly esteemed by those in control of the upper echelons of culture and became an important guiding principle of the Chinese patriarchal system. In practice and implementation, the idea of the Shinto religion consisted of two elements, one was “to revere the Shinto, to offer sacrifices to heaven and earth, to worship the ghosts and gods; the other was to promote education, to clarify rituals and good customs.” [6] The origins of Shinto have been variously interpreted by literati and scholars from ancient times to contemporary scholars. As for its original meaning, I agree with Wang Fuzi of the Qing Dynasty: “The principles of the Way of Heaven are rigid and uncompromising, and it includes all of nature as well as gods. The four seasons, the cold, the summer, the wind, the thunder, the frost, and the snow, are all induced by the yin qi, which moves in a smooth manner without fail.” [7] In this context, he defines the divine way as natural laws, implying that the “divine way” known by ancient society should be the cosmic laws collected by humans since ancient times. “System of the Book” (Zhou Yi: Hsi Tsu (The book of changes: Commentary on the Appended Judgments)) says: “The unpredictability of yin and yang is called the divine” and “When the door opens and shuts, people use it to enter and leave without understanding why, so they refer to it as a deity.”

Therefore, the way of yin and yang in nature is the “divine way,” and those who know these natural laws can guide people to follow the heavens and the times, and they are called “sages.” The ancient kings also taught the people to follow the natural ways of the heavens, in order to create a sense of obedience to the king’s authority in the hearts of the people, and thus achieve orderly governance of the country.

In this sense, the idea of “naturalism and moral righteousness” in the ZhouYi was a political philosophy that united naturalism and moralism, and at the time was very advanced political thinking with a strong sense of practicality. It was on the basis of the infectious power of this political thinking that the idea of Shintoism was transferred, especially since the two Han dynasties, “With the impact of the religious Confucianism of Dong Zhongshu and Liu Xiang and the infiltration of the former Han dynasty school of Confucian scholars 今文经学and divination, this theory gradually changed from the meaning of the king ruling the country in accordance with the mandate of heaven to a way and method of the king using ghosts and gods to rule and educate the people, and gradually transitioned from a realistic political theory to generalized religious instrumentalism, with its rational meaning weakening.”[8]

This is what Mr. Feng Youlan said in his work on the History of Chinese Philosophy: “Dong Zhongshu's proposition was put into practice, and the era of ziology (Study of A Hundred Schools of Thought 子学)ended; Dong Zhongshu's doctrine was established, and the era of scripture (Classics Scholarship 经学) began. The doctrine of the five elements of yin and yang was integrated with Confucianism until Dong Zhongshu achieved a systematic expression. Since then, Confucius has become God, and Confucianism (Confucian 儒家) has become Confucianism.”[9]

Internal factors and External influences in the Evolution of Chinese Folk Concepts of Creation - The Art of Paper Cutting by Gao Fenglian as an Example

by Liang Zhu *

School of Art and Design, Tianjin Tianshi College, Tianjin, China

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

JACAC. 2023, 1(1), 18-26;

Received: May 16, 2023 | Accepted: June 16, 2023 | Published: June 24, 2023

Introduction

Gao Fenglian (February 19, 1936 - January 20, 2017), a native of Yanchuan, Shaanxi, was a famous paper-cutting artist and the inheritor of the national intangible cultural heritage (Yanchuan paper-cutting). She started studying paper-cutting with her mother at the age of ten, and for more than a half-century, she made remarkable accomplishments in the areas of paper-cutting, cloth pile painting, and other folk arts with her diligence and extraordinary artistic endowment.

Gao Fenglian's paper-cutting is rooted in the deep and simple culture of the Yellow River and Loess in northern Shaanxi, reflecting the local people's simple sense of life and reproduction and expressing the natural concept of “Yin and Yang coming together to create all things, and all things coming to life.” Gao Fenglian's own hardships and optimistic character inject a constant source of energy and spirituality into her paper-cutting works.

What is even more remarkable is that Gao Fenglian, who cannot read or write, transforms the cultic concepts and auspicious cultural expressions inherited from her ancestors into realistic depictions of life. In other words, the “realism” in Gao Fenglian's paper-cutting works is a negation of the traditional “transcendentalism” of Chinese folk women's paper-cutting based on the cult of faith, and her “realism” has consciously achieved “modernity” in the evolution of Chinese folk women's paper-cutting concepts. It is a model for Chinese folk art to move towards modernity within its own system.

Rational consciousness: the awakening from primitive worship

If nature worship (including the sun, moon, stars, wind, rain, and thunder), totem worship (animals and plants), and reproductive worship (from female genitals to male genitals) are the superficial contents of primitive philosophy and culture, then the goblet (origin) of its conceptual change can be said to be the prehistoric rock paintings with their numerous images depicting human activities, such as hunting, herding, warfare, and rituals (sacrifices). The concern for the self was the internal motivation for the evolution of the concept of primitive worship.

Since the Shang and Zhou Dynasties, the rational component of our ancestors’ thinking system has gradually determined a new understanding of the universe, including the nature of the natural world and human beings. The era of myths and legends became history, and the sages of the pre-Qin era further refined the perceptual or psychological patterns of the original philosophy, forming the basis of the wisdom of ancient Chinese civilization - the expression “Yin and yang,” which represents the wisdom of the entire nation. The “Yin and Yang” is the foundation of ancient Chinese wisdom, representing the nation's awakened consciousness. Yizhuan (Commentaries of Yi), Dao De Jing (The book of the way), Chuang-Tzu ( A Taoist Classic), and Confucianism of Confucius and Mencius all emerged from prehistoric ideas, and the primitive Chinese cultic beliefs gave way to a “rational consciousness with a distinct pragmatic orientation and sense of history, or rather the primitive cultural ideas as a whole were exploited by a rational consciousness that upheld the patriarchal social system.” [1]

Labor and praying to the gods: the dual drive of the material and the spiritual

The intrinsic motivation for the change of concept began with the advancement of human productive capacity. The perfection of iron farming tools from the Western Zhou to the Warring States, and the spread of oxen farming from the Spring and Autumn Period to the Western Han Dynasty, all further increased people's affirmation of their own abilities, and their sense of awareness of self-needs seeped into their sense of worship, gradually changing their relationship with nature from passive to active, from worshipping natural forces to venerating earthly heroes, from believing in the sacred world to aspiring to worldly prosperity.

At the same time, people have become more aware of the important role that labor plays in changing their lives. Therefore, rural folk art eulogizes labor and denounces laziness, and they put this respect for labor into legends, folk proverbs, and folk songs, forming a conscious convention of folk morality.

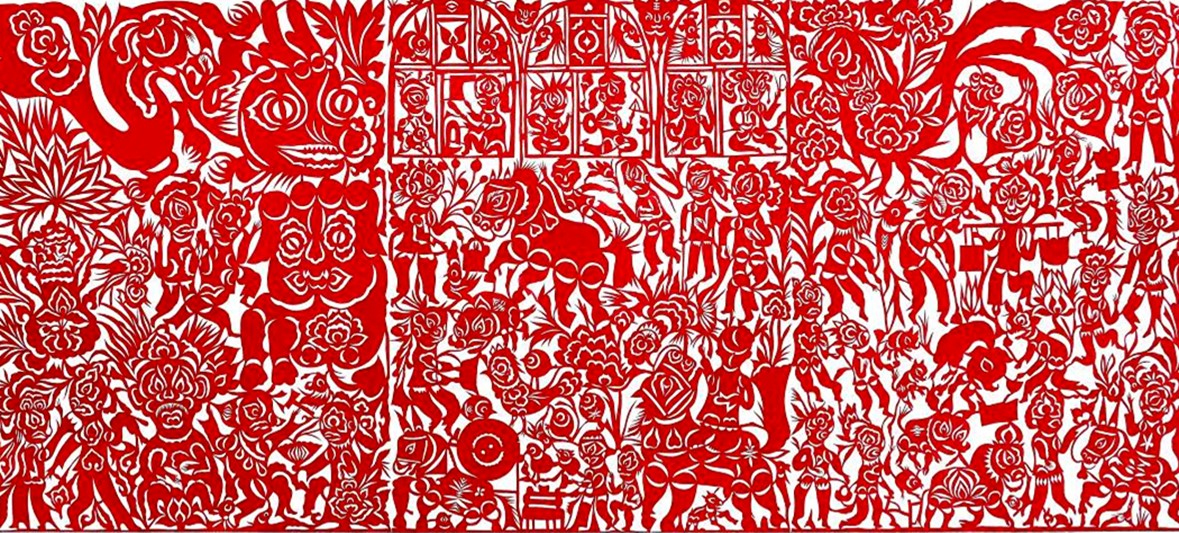

In 2000, Gao Fenglian won a special award at the Century Retrospective Exhibition of Chinese Folk Paper Cutting held at the National Art Museum of China for her work, which depicted rural people plowing, diving, pushing mills, riding and feeding horses, as well as women cooking, spinning and embroidering, and other laboring activities such as Gao Fenglian’s paper-cutting is an important theme in her work, as are special depictions of labor such as “feeding pigs”, “weaving” and “waiyao”. (other special depictions of labor, such as “feeding piglets,” “weaving,” and “waiyao,” is a major theme in Gao Fenglian's paper-cutting.) (Figure 1)

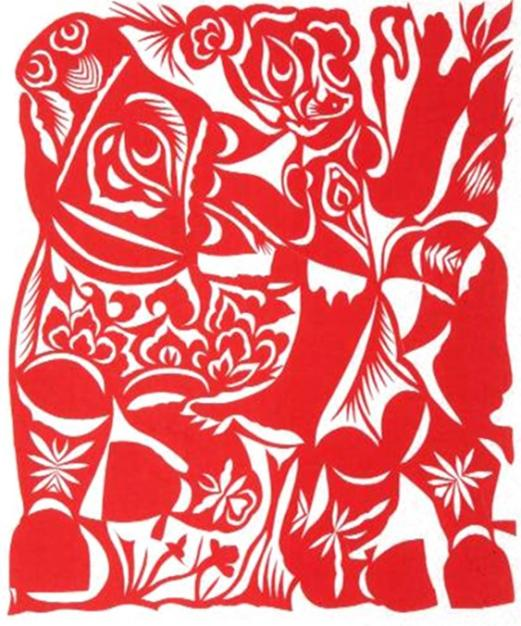

The reason for the importance of labor in folk culture and art is that it is how human beings themselves can manipulate themselves, and it is the only means of coping with powerful nature, and worshipping on demand what they are “powerless” to change reflects the initiative of the other side of the subject of people's consciousness. Gao Fenglian’s work The Heavenly Drum (Figure 2) reflects this kind of worship in real life: “When the heavenly drum sounds, the world is at peace; when it does not, the world is in chaos.” On the first day of every year, the whole village gathers to beat the drums and pray for good weather and rain throughout the year, and for the prosperity of both people and animals. The only thing the folk could do about the changing times of the sky and the rain and shade was to pray that they would follow the laws of their own production. So, we can see that Gao Fenglian could slowly make her family's “good fortune” with a lifetime of hard work, but in times of disaster she would also go to a nearby temple and burn incense to pray to the gods; so, we can see the respect for the various gods and goddesses in her paper-cutting works.

Abstract

Chinese folk decorative art embodies elements common to the living environment and everyday life. Among these, Gao Fenglian's paper-cutting is a model of Chinese folk art moving towards modernity within its own system, and the conceptual flux embodied in its works is based on the dual motives of Chinese folk art's own interpretation; labor and blessing promote the inherent self-confidence power of folk life, and ritual indoctrination (edification in rites and music礼乐教化) and Shinto establishment are an inevitable result of the statute of folk culture by the higher culture; Chinese folk cultural concepts and cultural spirit are formed under the dual role of the growth of the original culture and the need to stabilize the social structure, a process of flux and ritual indoctrination in reproduction.

Author Contributions

The author has written the article alone without committing plagiarism.

Funding

[This article is a stage result of the 2021 Beijing Federation of Literary Associations Basic Theory Research Project, Research on Jin Zhilin's Original Culture System and Artistic Creation (Project No. BJWLYJB05)].

Conflicts of Interest

The author has no conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

References

1. Lv Pintian, Concepts of Chinese Folk Art, Hunan Fine Arts Press, Changsha, 2007, p. 163.

2. Ibid [i], p. 169.

3. He Chancui, 'Examination of Ritual and Education', Modern University Education, 2010.4.

4. Duan Zicheng, 'A Study of the Officially Run Township Covenant in Northern China during the Qing Dynasty', China Social Science Press, Beijing, 2009.1.

5. Zhong Jingwen, ed: "Introduction to Folklore", Higher Education Publishing House, Beijing, 2010, p. 3.

6. Zheng Wangong, "An Examination and Interpretation of the Sayings of 'Shen Dao Sets up a Religion'", Zhou Yi Studies, 2006.2.

7. [Qing] Wang Fuzhi, "Shuanshan Quanshu (Book 1) - Zhou Yi Nei Zhuan", Yuelu Shushe, Changsha, 1996, p. 201.

8. Wu Hong, "The Literal Meaning of 'Shinto Set-Up Teaching' and Its Deduction", Journal of Zhongshan University Series, 2006, vol. 26, no. 8.

9. Feng Youlan, A History of Chinese Philosophy, Shanghai: East China Normal University Press, 2000, p. 25.

10. Jin Zhilin, Chinese Folk Art, Wuzhou Communications Press, 2004.8, p. 7.

© 2023 by the authors. Published by Michelangelo-scholar Publish Ltd.

This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND, version 4.0) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which per-mits non-commercial use, distri-bution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited and not modified in any way.

Article Metrics

Waiting for update.

Share and Cite

Chicago/Turabian Style

...

AMA Style

...

Table of Contents

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Rational consciousness: the awakening from primitive worship

- Labor and praying to the gods: the dual drive of the material and the spiritual

- Edification in rites and music and Shintoism: the rules from the upper culture

- Conclusion

- Author Contributions

- Funding

- Conflicts of Interest

- References

Folklore encompasses everything from production, food, clothing, housing, transport, festivals, folk entertainment, folk beliefs, marriage rituals, folk proverbs, folk tales, myths and legends, songs, and chants, and so on. The transmission of folklore is somewhat non-compulsory, especially in the category of folk art, which has a strong function of “music and education” and can accomplish the teaching of “rites” in entertainment.

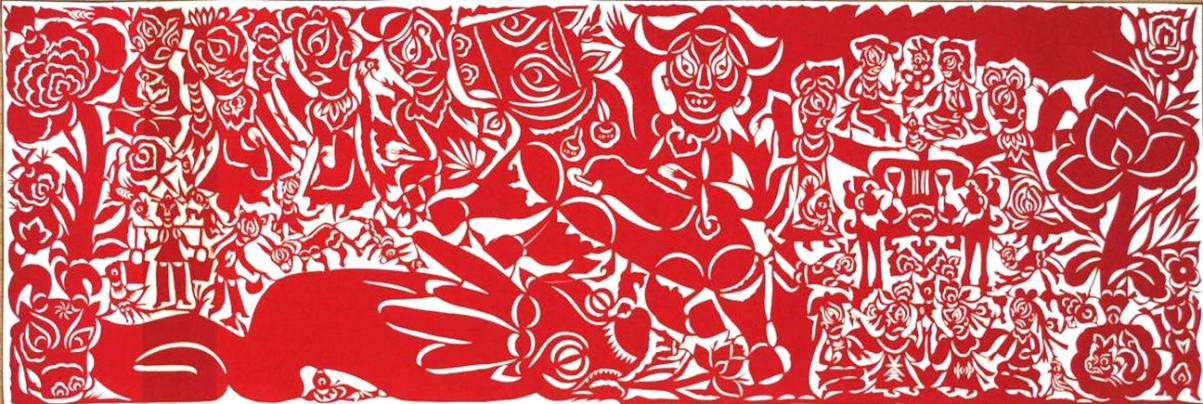

Gao Fenglian’s paper-cutting works are rich in folk songs, ballads, stories, and legends, and to a certain extent they can be used as typical material for the realisation of “music and education” in Confucianism. For example, Zhang Zongdao Marries a Wife (Figure 4) tells the story of a loyal, kind, and filial man who is eventually rewarded with good fortune - his filial piety moves the river god, who then marries his daughter, the “River Lady,” to Zhang Zongdao. In the scene, the dragon is coiled into a river, and peonies appear in a vase on either side, meaning “to embrace the grandchildren of the family.” It is feared that similar folk tales were told all over ancient China, with the Confucian idea of filial piety, righteousness, and loyalty as the aim of education, and that the result of goodness and loyalty was more than ordinary glory and wealth, both in the form of a wife and children and a glorious family.

The story of Jin and Yin is about their father who became a big official and married a new wife. Jin's grandma then dispatched his mother, sister, and him to the tile kiln in front of Shuangma Temple, where they endured starvation and thirst. Later, when Jin became more and more sensible, he was determined to find out where his father was, and asked his mother for a “gold, copper, and silver sweatband” - a token he had left for his mother when his father went to the capital to participate in the imperial examination - and finally (eventually) the family was reunited when they found their father. (Figure 5 & 6)

The pattern of edification of folk consciousness by the power structure in Chinese society remained consistent throughout the dynastic shifts that followed. The integration of Buddhism and Taoism into the mainstream of social consciousness enriched the choices made by successive ruling classes according to their own needs. It was also from the two Han dynasties that Chinese society gradually moved from primitive worship to a state of artificial religiosity, from the moral constraints of “loyalty, filial piety, ethical, and righteousness” and “comeuppance” to the realistic expectation of “happiness, prosperity, and longevity (luck and wealth and longevity and happiness).” A series of ethical concepts of “goodness” penetrated the souls of the common people, and the accumulation of good deeds was the way to realize their aspirations. (Figure 7)

The humanistic spirit of all this “transformation” allows us to see that their desire for life and children is expressed in folk art not as a naked carnal desire, but as a poetic symbol; their desire for wealth and prosperity is not through blood and fire, but through hard work; their fear of unpredictable natural and man-made disasters is not negative and pessimistic, but rather with a positive response that transformed attitudes and sought reliance.

In light of the above discussion, we say that Chinese folk cultural concepts and cultural spirit were formed under the dual role of the self-propagation of the original culture and the need to stabilize the social structure, as a process of flux and ritual edification in reproduction.

Conclusion

In summary, the creation of folk art is a process of 'transformation' of the humanistic concepts and humanistic spirit of the ordinary working masses on the basis of their original philosophy. Chinese folk cultural concepts and spirit are formed under the dual role of the self-propagation of the original culture and the need to stabilise the social structure and are a process of change and ritualistic indoctrination in the process of reproduction.

In the midst of China's comprehensive modernisation quest many folk cultures and arts are facing a crisis of inheritors and mass discontinuity. Although many scholars have examined the sequential relationship between the practical and aesthetic aspects of human creation from a variety of disciplines, this is not the key to our exploration of the survival of folk art. Thinking about the aesthetic needs of promoting or reviving folk art is often based on the logical reasoning of studies of its utilitarian nature. As traditional rural life enters industrial civilisation, this logic will also reason out the demise of folk art as utilitarian ideas such as survival, profit and avoidance of harm recede in the folklore.

It is true that folk art has a certain commodity value in its utilitarian orientation, but commodity is not a value to be pursued in folk art. Folk art is "the art of visual images created by the Chinese folk masses to meet their own social needs", "it is the art of the producer, not the art of the professional artist", and "it is not created for commodity production or social and political needs". 10 Today, in the protection and inheritance of traditional folk art, excessive commercialisation will lead to the industrialisation of folk art, thus detaching it from its original cultural context and losing the spirituality and moving nature of folk art itself; it will also be like ordinary commodities, where market demand determines the direction of production and economic efficiency determines the motivation for its creation. Not only is this not the direction of survival and development of folk art, but it is also a problem that we need to correct after the industrialisation of culture. Can the industrialisation of culture lead to the revival of civilisation and the enhancement of cultural character? The truth is that what we see today is more of a "vulgarisation". If the 'industrialisation' of traditional folk culture is intended to bring it into line with modern society, then the first place to start is the study of how to resolve the conflict between the local consciousness of village life and the mainstream of contemporary culture.

Lates articles