3.2. The Technological Instrumental Layer: A Political Topology for Counter-Hegemonic Interfaces

Contemporary urban spaces are undergoing unprecedented technological innovations, where digital technologies and big data are transforming urban societies and everyday life in unprecedented ways. Focusing on the technological instrumental layer, this chapter explores how a counter-hegemonic politics of visibility can be realized through dynamic media façades and data-driven interfaces, and how these technological practices can reveal and challenge existing power structures. By combining these technological practices with social theory, we can construct a new type of political topology that offers new possibilities for the democratization and equity of urban space.

3.2.1. Dynamic Media Facade: The Politics of Visibility and the Reverse Use of Landscape Critique

The mechanism of the “politics of visibility” of the dynamic media façade as an important technological tool in contemporary urban space can be traced back to French thinker Guy Debord’s critical theory of the “landscape society.” In his book The Landscape Society, Debord points out that in contemporary capitalist societies, real social relations have been transformed into representations and commodities, and people are so mesmerized by these landscapes that they no longer pay attention to reality [22]. According to Debord, the essence of the landscape society, as the latest form of contemporary capitalist development, lies in the representation of social existence and the loss of people’s demand for an authentic life due to their fascination with the landscape.

However, the dynamic media façade applies Debord’s critical theory in reverse. By transforming abstract data into intuitive visual representations, the dynamic media façade makes the invisible visible, thereby revealing rather than obscuring reality. For example, by transforming carbon emissions data into light intensity gradients, environmental problems such as industrial pollution are visually mapped, enabling the public to clearly perceive the state of the environment. This technological practice forms an interesting dialectical relationship with Foucault’s theory of “disciplinary power.” Foucault’s “disciplinary power” refers to forms of power that control groups of people through discipline and norms [23]. The dynamic media façade enables people to see and challenge these power structures by transforming this form of power into a “resistant visualization.” This process of transformation transforms the technological tools originally used for control into means of revelation and resistance.

From the perspective of Latour’s Actor Network Theory (ANT), the dynamic media façade creates a network of non-human actors comprised of sensors, algorithms and citizens [24]. In this network, traditional centers of power are dismantled and power becomes more transparent and democratized. Sensors collect environmental data, algorithms process and analyze the data, and citizens become an important part of this network through interaction and participation. The structure of this distributed network allows power to be less centralized in a single entity and more dispersed among multiple actors, thus achieving a challenge to the traditional centers of power.

3.2.2. Data-driven Interfaces: Revealing and Reverse Engineering Topological Violence

The “topological violence” of data-driven interfaces reveals mechanisms that are essentially reverse-engineered using Deleuze’s theory of the “control society” [25]. Deleuze’s concept of the “control society,” in contrast to Foucault’s “regulation society,” suggests that control in contemporary societies is more fluid and flexible, not relying on fixed institutions, but rather managed through algorithms and data-driven systems. By revealing the power dynamics and potential for violence in such controlled societies, data-driven interfaces allow us to question and challenge these power structures. Specifically, machine learning’s cluster analysis of patterns of public space use can deconstruct the logic of spatial exclusion in David Harvey’s process of “capital urbanization” [26]. Harvey’s concept of “capital urbanization” refers to how capitalism reshapes urban space through the process of urbanization, often marginalizing and excluding certain groups. Data visualization methods such as heat maps can expose the invisible colonization of street space by commercial capital, thus revealing inequalities in the use of space. An alternative perspective is provided by Doreen Massey’s spatial rectification schemes based on the geography of difference. Massey’s geography of difference emphasizes that space is constituted by different social relations and differences, rather than being homogeneous [27]. Spatial rectification programs consider the social and cultural dimensions of space and seek to address exclusion by proposing more equitable and inclusive uses of space.

3.2.3. Summary: Critical Practices and Democratic Potential in the Technological Instrumental Layer

The technological instrumental layer, as a bridge between technological practice and social critique, plays a key role in constructing a political topology of counter-hegemonic interfaces. Through dynamic media façades and data-driven interfaces, we are able to reveal hidden power structures and inequalities, challenge traditional centers of power, and promote a more transparent and democratic society. These technological practices are not only a technical tool, but also a political practice that offers new possibilities for social change by changing the way we perceive and understand urban space.

By combining theoretical frameworks such as Debord’s landscape critique, Foucault’s theory of disciplinary power, Latour’s theory of actor networks, Deleuze’s theory of the control society, Harvey’s theory of the urbanization of capital, and Massey’s geographies of difference, with contemporary technological practices, we can construct a new kind of political topology that offers new perspectives and approaches to democratization and fairness in urban space. This political topology focuses not only on the development and application of technological tools, but also on how these tools are shaped by social forces and how they in turn affect social structures and power relations. Through critical reflection and practice, we can make technological tools serve social justice goals and open up new possibilities for fairer and more democratic urban spaces.

Innovation School of the Great Bay Area, Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts, Guangzhou, China

* Author to whom correspondence should be addressed.

JAUD. 2025, 2(1), 95-117; https://doi.org/10.59528/ms.jaud2025.0906a6

Received: April 28, 2025 | Accepted: July 20, 2025 | Published: September 6, 2025

Haoyi Ruan

by

Beyond Screens: Towards a Just Transition Framework in Media Architecture through Digital-Physical Hybridity

3.3. The Media Ethics Layer: A Three-Dimensional Tension Structure for Environmental Justice

Environmental justice, as a core issue facing contemporary society, has extended its connotation beyond the traditional scope of environmental protection to multiple dimensions such as social equity, technological ethics and media responsibility. In the context of the deep integration of digital technology and the physical environment, the media ethics layer, as an intermediary connecting technology and environmental justice, presents a three-dimensional tension structure of procedural justice, distributive justice and recognition justice. This report will explore in depth the specific manifestations of this three-dimensional structure in the media ethics layer, analyze its theoretical basis and practical application, and provide reference for the construction of a media ethics framework for environmental justice.

3.3.1. Algorithmic Implementation of Procedural Justice

Procedural justice, in the field of environmental data collection and processing, emphasizes the ability of all stakeholders, especially vulnerable groups, to participate fairly in and influence decision-making processes. Rawls’ theory of the “curtain of ignorance” provides a theoretical basis for this goal, which proposes that principles of justice should be designed without knowledge of one’s position in society in order to ensure fairness [28]. In an algorithmic environment, this idea translates into the mechanism of the “algorithmic curtain,” which aims to ensure that the ecological claims of disadvantaged groups are given equal weight when processing environmental data.” The “algorithmic curtain” serves as a procedural safeguard mechanism to ensure fairness in the decision-making process by implementing specific computational strategies at the algorithmic level to ensure that the data processing process is not influenced by factors such as the user’s social identity and economic status. This mechanism draws on the core idea of Rawls’ theory of making decisions without knowing one’s specific social location to ensure universal applicability and fairness in decision-making.

Achieving equal weighting of ecological claims of disadvantaged groups while protecting privacy, differential privacy technology offers a key solution in which media architecture can play a role. Differential privacy is an approach that protects individual privacy while still allowing data to be analyzed by adding noise to the data, preventing the disclosure of personally identifiable information while maintaining the statistical properties of the data. In media-built environment data collection and analysis, the application of differential privacy techniques under control technology ensures that data from vulnerable groups are not overused or discriminated against. For example, when calculating air pollution indices for aboriginal settlements, algorithmic curtains combined with differential privacy techniques ensure that the data from these communities are fairly weighted and not ignored or underestimated due to their disadvantaged status. In this way, privacy is protected while ensuring the fair expression of ecological claims.

3.3.2. Energy Politics of Distributive Justice

Distributive justice, in the area of energy production and distribution, is concerned with the equitable distribution of resources, in particular ensuring that disadvantaged groups have access to the energy resources they need. Horton’s “fair share” urban model emphasizes that the distribution of urban resources should be based on a fair share for each community or group, ensuring that everyone has access to the resources to which they are entitled. This model focuses on equity in the distribution of urban resources and advocates a scientific and rational allocation mechanism to ensure that each community has access to resources that match its needs and contributions. Jeremy Rifkin’s theory of “energy democracy” advocates the decentralization of energy production, enabling individuals and communities to produce energy on their own and reduce their dependence on centralized energy producers [29]. This theory emphasizes the importance of democratizing energy, arguing that energy production should be in the hands of more people, rather than centralized in a few large corporations or institutions. The theory of energy democracy suggests that decentralization of energy production can be achieved through distributed energy production and microgrid systems, enabling communities and individuals to manage energy production and distribution on their own, thus breaking the traditional energy monopoly pattern and promoting energy democracy.

In the media architecture, the integration of the “fair share” urban model and the theory of “energy democracy” is manifested in the integration of the photovoltaic façade and the microgrid system. By adopting photovoltaic technology, the media architecture transforms the building surface into a place of energy production, while at the same time realizing the local distribution and management of energy through the microgrid system. This design makes the media architecture not only a vehicle for information dissemination, but also a participant and manager of energy production. Through the photovoltaic façade, the building can utilize solar energy to generate electricity, reducing the reliance on traditional energy sources; through the microgrid system, the building can achieve local storage, distribution and sharing of energy, forming a closed loop of energy production and consumption. By integrating a photovoltaic façade and a microgrid system, the media architecture provides disadvantaged communities with access to and use of renewable energy, reduces reliance on traditional energy suppliers, lowers energy costs, and improves access to energy. The design contributes to the viability of disadvantaged groups, enabling them to better meet their basic needs, participate in socio-economic activities and achieve personal development.

3.3.3. Interface Design for Recognizing Justice

The application of recognition justice in interface design is based on Nancy Fraser’s theory of the politics of recognition. Fraser argues that recognition is the key to addressing oppression and discrimination, and that by recognizing the social identity, dignity, rights, and worth of others, oppressive relationships in society can be broken down and social justice promoted [30]. In the field of interface design, recognition justice requires that we design interfaces that respect and acknowledge the needs, abilities, and identities of diverse users, especially those groups that have been historically marginalized or ignored. Multimodal interactive interfaces need to integrate perceptual compensatory technologies such as sign language recognition (serving the deaf community) and scent feedback (serving the visually impaired) to break down the ableism criticized by Martha Nussbaum. These technologies are designed to compensate for the user’s perceptual impairments in vision, hearing, etc., and allow them to effectively interact with the interface through other sensory channels. Sign language recognition technology allows deaf users to communicate with interfaces through gestures, enabling them to participate in conversations and access information and services. Odor feedback technology, on the other hand, provides visually impaired users with a new way of perceiving information, enabling them to access environmental information through the sense of smell and enhancing their ability to interact with the environment.

3.3.4. Summary: Integrated Analysis of Three-Dimensional Tension Structures

Procedural justice, distributive justice and recognition justice form a complex structure of tension at the level of mediated ethics. These three forms of justice are not independent of each other, but are interrelated and interact with each other. Procedural justice is concerned with the fairness of the process, ensuring that disadvantaged groups are able to participate in the decision-making process; distributive justice is concerned with the fair distribution of resources, ensuring that disadvantaged groups have access to the resources they deserve; and recognition justice is concerned with recognizing the identity and needs of disadvantaged groups, ensuring that they are respected and recognized. Together, the three forms of justice form a complete picture of environmental justice. There are tensions between these three forms of justice. For example, overemphasis on procedural justice may lead to formal fairness but substantive inequality; overemphasis on distributive justice may lead to neglect of procedural fairness; and overemphasis on recognition justice may lead to overprotection of disadvantaged groups, affecting overall fairness. Therefore, there is a need to balance these three forms of justice in the media ethics layer to form a dynamic and balanced structure.

Media ethics plays a key role in environmental justice. The media is not only a carrier of information dissemination, but also a constructor of social power and discourse. Through the media, the concept of environmental justice can be spread, environmental problems can be paid attention to, and environmental policies can be formulated and implemented. At the level of procedural justice, the media promotes public participation in the environmental decision-making process through reporting and commenting, ensuring the transparency and participation of the decision-making process. At the level of distributive justice, the media promote the fairness of resource distribution by revealing the inequality in the distribution of environmental resources. At the level of recognition justice, by focusing on and reporting on the environmental claims of vulnerable groups, the media enhance social recognition of and respect for these claims.

3. Preliminary Construction of a Theory of Service Media Architecture

3.1. Theoretical Layer: Dialectical Coupling of Media Ecology and Spatial Production

As an emerging form of urban space, the revolution of media architecture does not lie in the simple application of technology, but in its dual material-digital properties as a “Third Space.” This dual property makes media architecture an important vehicle for understanding the dialectical relationship between media ecology and spatial production. Starting from this chapter, the theoretical foundations of media architecture will be explored in depth, revealing how it reconfigures urban perceptual patterns through real-time data streams. At the same time, the study will examine the media evolution from knotwork to LED façades from the perspective of media archaeology, revealing the connection between this evolutionary process and the exponential increase in the degree of visualization of spatial power. In addition, how the “haptic democracy” created by interactive urban screens breaks the Bennettian “sensory hierarchy” through the embodied cognition of interface touch and enables marginalized groups to gain a voice in spatial narratives will also be an important part of this study.

3.1.1. Media Architecture as a Third Space

Soja proposed the theory of “Third space”, the basic purpose of which is to transcend the dichotomy between the real and the imagined, and to grasp space as a synthesis of differences, a “complex domain of associations” that changes in appearance and meaning with the changes in cultural and historical contexts [16]. According to Soja, there are three types of space: material space, imaginary space, and living space, of which living space is the third space that Soja strongly elaborates. The theory of the third space is a theoretical result achieved by Edward Soja by taking Lefebvre’s triad of spatial production as a starting point and combining it with years of postmodern critical research on urban space. The basic path of the theory is based on Lefebvre’s triadic dialectic of spatiality and further develops the postmodern critical research on urban space.

The revolutionary nature of media architecture as a third space lies in its dual material-digital properties. This dual attribute makes media architecture a hybrid space between physical reality and digital virtualization, breaking the dichotomy between traditional physical space and digital space. The dynamic media façade reconfigures the city perception mode through real-time data flow, upgrading Corbusier’s “living machine” to a “perceiving machine.” This transformation not only changes the way people perceive the city, but also changes the way urban space is produced. Media architecture is no longer just an extension of physical space, but a new mode of spatial production, integrating material space with digital space to create a new third spatial experience.

3.1.2. Medium as Interface: from McLuhan to Architecture as Interface

The theory of “the medium is the message” put forward by McLuhan is a high-level generalization of the status and role of the media in the development of human society. The implication is that the medium itself is the real meaningful message. That is, human beings can only perceive and understand the world when they have some kind of medium. In his book Understanding Mediums: on the Extension of Man, McLuhan suggests, “in a social sense, the medium is the message.” The view we usually take is that the medium is just a tool, a vehicle, and the message it carries is what we really need, what has a major impact on this society [17]. The medium itself is the most valuable message. In the context of media architecture, McLuhan’s theory of “medium as message” evolves into “architecture as interface.” This means that media architecture itself is no longer just a physical structure, but an interface between people and the digital world. This shift transforms architecture from a mere provider of physical space to a purveyor of information and a medium of interaction. Through its dynamic nature, media architecture becomes a new type of medium in urban space, changing the way people interact with urban space.

3.1.3. Triadic Dialectics of Spatial Production and Media Architecture

Lefebvre’s theory of spatial production consists of three interrelated aspects: representational space, spatial practices, and space of representations. Representational space is the cultural and ideological manifestation of space; spatial practices are the actual interactions and activities of people in space; and space of representations is the political and economic structure of space that shapes its use and representation [18]. Lefebvre’s triadic theory of space is Lefebvre’s re-conceptualization of space in capitalist societies from a spatial-political point of view, and is manifested in the revelation of ‘fragmented space’ under the capitalist mode of production, which is mainly characterized by the division of labor, and the relationship between capital accumulation and spatial reconfigurations.

In media architecture, data-driven spatial interfaces (space of representations) and the citizens’ interactive behaviors (spatial practices) are interwoven in the framework of policy (space of representation) are intertwined, leading to a dynamic reconfiguration of power relations through light and shadow encoding and algorithmic decoding. This dynamic interaction makes media architecture a site of power and information flows that shape public opinion and behavior. Through its dynamic nature, media architecture combines data-driven spatial interfaces with citizens’ interactive behaviors to form a new model of spatial production within a policy framework. This model allows spatial power to be dynamically reconfigured through light and shadow coding and algorithmic decoding, thus changing the traditional way spatial power operates.

2. Case Study of Media Architecture as Service Design

In the International Media Architecture Biennale, there is a classification of media architecture, and one of the important branches is participatory architecture, in other words, the façade or space of a building is understood as a participatory platform, and at the same time, the building transforms itself into an interactive machine that can be controlled and debugged. This chapter will select representative cases under this categorization to explore the ways in which media architecture is designed as a service and the specific forms of expression.

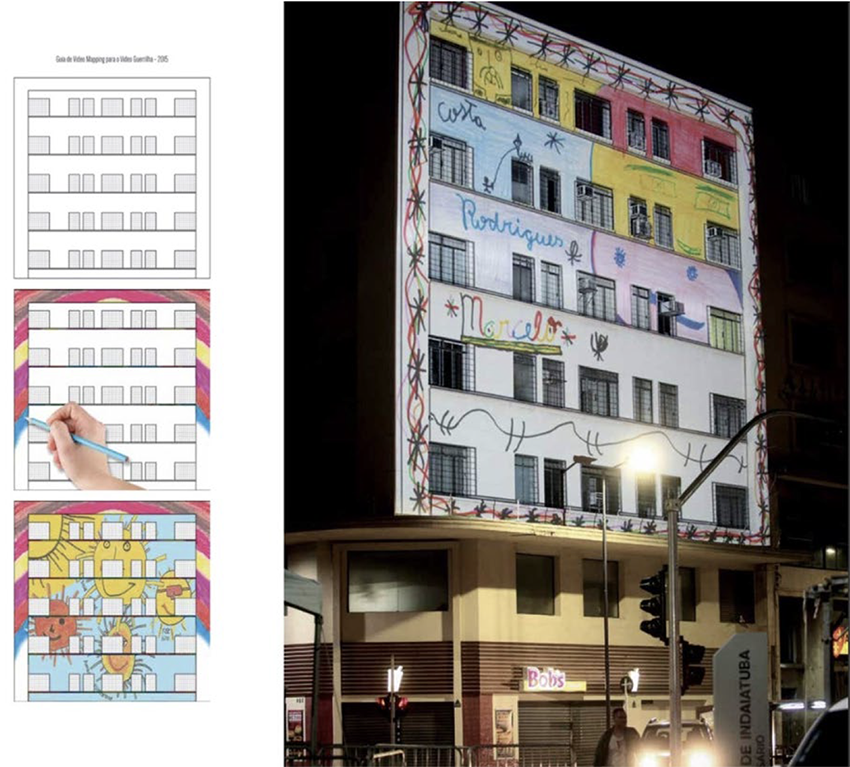

2.1. Amplifying Marginalized Voices

The 3-kilometer viaduct built in downtown São Paulo, Brazil, in the 1960s relieved traffic pressure but led to the area’s decay due to noise pollution. After a long struggle by the residents, the viaduct’s hours for automobile traffic were compressed (open weekdays from 7:00 to 20:00) and the rest of the day was transformed into a pedestrian park. As depicted in Figures 1a and 1b, artist Alexis Anastasiou collaborated with four other creators to organize a participatory media art exhibition and screening during this period. He was pivotal in guiding the public through an immersive nighttime event, which combined walking and viewing. At the end of the project, the municipality officially confirmed the time-limited pedestrianization of the space.

Share and Cite

Chicago/Turabian Style

Haoyi Ruan, "Beyond Screens: Towards a Just Transition Framework in Media Architecture through Digital-Physical Hybridity" JAUD 2, no.1 (2025): 95-117.

AMA Style

Ruan HY. Beyond Screens: Towards a Just Transition Framework in Media Architecture through Digital-Physical Hybridity. JAUD. 2025; 2(1): 95-117.

© 2025 by the authors. Published by Michelangelo-scholar Publishing Ltd.

This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND, version 4.0) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited and not modified in any way.

References

1. Bridges, A., and D. Charitos. “On Architectural Design in Virtual Environments.” Design Studies 18, no. 2 (1997): 143–154. [CrossRef]

2. Shostack, G. L. “How to Design a Service.” European Journal of Marketing 16, no. 1 (1982): 49–63.

3. Hollins, G., and B. Hollins. Total Design: Managing the Design Process in the Service Sector. Pitman, 1991. [CrossRef]

4. Holopainen, M. “Exploring Service Design in the Context of Architecture.” The Service Industries Journal 30, no. 4 (2010): 597–608. [CrossRef]

5. Bell, B., ed. Good Deeds, Good Design: Community Service through Architecture. Princeton Architectural Press, 2004.

6. Ploger, J. “Urban Planning and Urban Life: Problems and Challenges.” Planning, Practice & Research 21, no. 2 (2006): 201–222. [CrossRef]

7. Wiethoff, A., and H. Hussmann. Media Architecture. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton, 2017. [CrossRef]

8. Caldwell, G. A., and M. Foth. “DIY Media Architecture: Open and Participatory Approaches to Community Engagement.” In Proceedings of the 2nd Media Architecture Biennale Conference: World Cities, 1–10, 2014. [CrossRef]

9. Sarsangi, M. “Street Theater and Its Relationship with Urban Spaces.” The Monthly Scientific Journal of Bagh-e Nazar 12, no. 34 (2015): 37–48.

10. Meroni, A., and D. Sangiorgi. Design for Services. Routledge, 2016. [CrossRef]

11. Lortie, J., K. Cox, S. DeRosset, R. Thompson, and S. Kelly. “Unpacking the Minimum Viable Product (MVP): A Framework for Use, Goals and Essential Elements.” Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development 32, no. 1 (2025): 212–235. [CrossRef]

12. Weeks, R. V. “Managing the Services Encounter: The Moment of Truth.” Journal of Contemporary Management 12, no. 1 (2015): 360–378.

13. Smith, P. D., G. Vanicor, M. Rowand, M. Hess, D. Yarbrough, J. Foret, et al. Ripple Effect. PD Smith, 2012.

14. Baltes, G., and I. Leibing. “Guerrilla Marketing for Information Services?” New Library World 109, no. 1/2 (2008): 46–55. [CrossRef]

15. Wark, M. Capital Is Dead: Is This Something Worse? Verso Books, 2021.

16. Soja, E. W. “Thirdspace: Journeys to Los Angeles and Other Real-and-Imagined Places.” Capital & Class 22, no. 1 (1998): 137–139. [CrossRef]

17. McLuhan, M. The Medium Is the Message. Routledge, 1967.

18. Lefebvre, H. “From the Production of Space.” In Theatre and Performance Design, 81–84. Routledge, 2012.

19. Marks, L. U. Touch: Sensuous Theory and Multisensory Media. University of Minnesota Press, 2002.

20. Marks, L. U., and D. Polan. The Skin of the Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses. Duke University Press, 2020.

21. Bennett, C. “Up the Hierarchy.” The Journal of Extension 13, no. 2 (1975): 2.

22. Debord, G. The Society of the Spectacle. Unredacted Word, 2021. [CrossRef]

23. Foucault, M. “Discipline and Punish.” In Social Theory Re-wired, 291–99. Routledge, 2023. [CrossRef]

24. Latour, B. “On Actor-Network Theory: A Few Clarifications.” Soziale Welt (1996): 369–381.

25. Deleuze, G. “Postscript on the Societies of Control.” In Surveillance, Crime and Social Control, 35–39. Routledge, 2017. [CrossRef]

26. Harvey, D. The Urbanization of Capital: Studies in the History and Theory of Capitalist Urbanization. 1987.

27. Massey, D. “Geographies of Responsibility.” Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 86, no. 1 (2004): 5–18. [CrossRef]

28. Runcheva, H. “John Rawls: Justice as Fairness behind the Veil of Ignorance.” Iustinianus Primus L. Rev. 4 (2013): 1.

29. Rifkin, J. The European Dream: How Europe’s Vision of the Future Is Quietly Eclipsing the American Dream. John Wiley & Sons, 2013.

30. Fraser, N. “Social Justice in the Age of Identity Politics: Redistribution, Recognition, and Participation.” In Geographic Thought, 72–89. Routledge, 2008.

“Yellow Dust” demonstrates the service design potential of media architecture as a socio-technical system through the reconstruction of environmental perception and the re-engineering of the closed loop of service, which is embodied in the following threefold logic. The shallow logic is embodied in the embodied translation of data services. The project transforms the digital monitoring of air pollution into an empathetic body experience through the water vapor and humidity sensory interface that includes the visual density of yellow mist, breaking through the cognitive barrier of the “data black box” in traditional environmental monitoring. This design strategy essentially shifts the user journey touchpoints in service design from screen interaction to environmental immersion—when the public walks through the yellow fog due to changes in pollution concentration, their respiratory rate, skin touch and visual impact together form a multimodal feedback system. This not only reconfigures the way the public understands environmental data, but also stimulates the individual’s willingness to participate in governance through the physiological arousal mechanism, forming a complete service chain of “perception-cognition-response.”

The middle logic is manifested in the service ecology incubation of open-source infrastructure. As an open-source urban facility, Yellow Dust’s DIY components and modularized architecture cede technical authority from professional organizations to the public, creating the possibility of growing distributed service nodes. The service system contains double openness. The technology layer manifests itself in the replicability of sensor solutions and building systems, allowing the community to customize solutions based on local pollution characteristics; the data layer manifests itself in the public nature of environmental monitoring data, facilitating the crowdsourcing of cross-regional pollution mapping. This design transforms the media architecture into a service prototyping toolkit, moving air governance from a centralized public service to a participatory network of services based on citizen science, fitting the core principle of empowering edge innovation in service design.

The deeper logic is reflected in the mediation of contradictions in the healing space. The project operates in a dual mode of “monitoring-repair,” exposing environmental problems while providing immediate relief, realizing the balance between critical and constructive service design. While visualizing the concentration of pollution, the water vapor system reduces the amount of suspended particulate matter through humidification and mitigates the heat island effect through cooling, forming a closed-loop service of “exposing trauma—implementing healing.” This dialectical spatial narrative breaks the unidirectional expression of the traditional media architecture as a cautionary tale, and instead builds a flexible service field with both problem revelation and solution, providing citizens with a smooth transition path from cognition to action.

The case corroborates the infrastructure-as-service interface theory proposed by service design scholar Daniela Sangiorgi—by transforming technological systems into perceptible and operable public interfaces, media architecture is able to reorganize the network of relationships between people, environments and technologies [10]. “Yellow Dust” is groundbreaking in that it creates an Affordance for environmental governance: the visual density of the yellow mist suggests the state of the air, the somatosensory feedback of the water vapor guides behavioral regulation, and the open-source architecture suggests the feasibility of public participation. This design makes invisible public service processes visible as interactive environmental syntax, ultimately elevating infrastructure from a functional container to a social innovation platform that catalyzes citizens’ collective wisdom.

2.3. Promoting Civic Activism in Decision-Making Processes

During the quarantine of the 2020 Coronavirus epidemic, São Paulo, Brazilian artist Alexis Anastasiou took advantage of the 270-degree view from the 20th floor of his apartment and took it upon himself to transform two projectors (a 12k laser and a 20k light bulb) into a makeshift protest installation (Figure 3a), projecting satirical images created in real time onto the façades of hundreds of residential buildings in the neighborhood, targeting Brazilian extreme right-wing President Bolsonaro’s weakening of the epidemic. Rhetoric. Using improvisational mapping techniques, these guerrilla projections quickly gained attention.

They superimposed images, described in Figure 3b, of the President’s “Little China Flu” declaration and his refusal to wear a mask. These projections spread via neighboring social media outlets. They soon captured both local and international media interest. Ultimately, they became a key visual symbol in the global awareness of Brazil’s political crisis during the pandemic. Using the building façade as a canvas, this zero-budget initiative reconfigured the potential for political expression in high-density urban spaces amidst spontaneous civic protests by banging on pots and pans.

Funding

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest related to this research.

▪ Haoyi Ruan is a lecturer in the Digital Humanities domain at the Innovation School of Greater Bay Area, Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts. He received his doctoral degree in Art and Design from the University of Wales Trinity Saint David (UK) in 2025. His primary research interests include media architecture and urban spatial innovation.

The case demonstrates the radical practice of media architecture as a self-organized service system for citizens, and its breakthrough lies in the construction of a decentralized public service network through the temporary expropriation of spatial media and the fission dissemination of social networks. Specifically, it can be deconstructed into three dimensions from the perspective of service design. The first dimension presents the civilianization of critical infrastructures, where the artist transforms a private apartment into a public service base station through reverse engineering thinking, restructuring of Paul’s equipment, spatial programming and risk avoidance. The artist uses office chairs, old stereos, and books to build a temporary projection stand, and ropes are fixed to realize the mobility of the equipment, breaking through the dependence of professional media architecture on fixed hardware; using a 270-degree field of view to establish a dynamic mapping relationship of “projection radius—building façade—resident’s window,” making the high-rise apartment a rotatable and adjustable urban projector. By instantly adjusting the projected target building, it balances the intensity of expression with the threshold of residents’ complaints, forming an elastic service agreement. The construction of this Citizen Infrastructure subverts the power structure of traditional media architecture that relies on capital and technology, and confirms the principle of “Minimum Viable Product (MVP)” in service design—the rapid validation of public service prototypes at the lowest cost [11].

The second dimension is expressed in the mechanism of real-time responsive content production, in which the project establishes the event character of the public service through the design of immediacy. The artist dynamically overlays presidential statements, news images and satirical texts to synchronize content production with social mood swings; chooses the 8 pm protest peak as the projection time to create audio-visual resonance with the residents’ action of banging pots and pans; and uses the attributes of the giant public screen on the façade of the building to naturally adapt to the format of cell phone photography for social media communication (e.g. vertical composition, high contrast). This mechanism upgrades the media architecture from a “spatial device” to a social event generator, which is in line with the theory of “Moment of Truth” in service design—providing precise and accurate information at the public’s emotional tipping point. This is in line with the theory of “Moment of Truth” in service design, which is to provide precise service touchpoints at the public’s emotional tipping point [12].

The third dimension is the construction of a distributed public service network, in which the project realizes the exponential expansion of the influence of public services through the nesting of spatial media chains and digital communication chains. The building façade serves as a primary node that carries the original image data; the neighbor’s cell phone shot transforms into a secondary node that is fanned out through social media; and the mainstream media citation forms a tertiary node that builds a global cognitive framework. This onion-like communication structure enables a single architectural projection to trigger a transnational public service network, confirming the ripple effect in service ecology—a strategic perturbation of the core touchpoints triggers a systemic service response [13].

This practice can be read within the framework of Guerrilla Service Design, whereby citizens autonomously construct alternative service systems through technological appropriation, spatial occupation, and immediate collaboration when institutionalized public services fail [14]. Its value lies not only in exposing the crisis of power, but also in demonstrating the possibilities of media architecture as political infrapolitics—the creation of Temporary Autonomous Zones in the space of disciplinary power and the transformation of urban interfaces into empathic networks of civic resistance. The urban interface is transformed into an Empathy Network of civic resistance. As media theorist McKenzie Wark puts it, “Creating visibility in the most unlikely places is itself an act of service to reclaiming the narrative power of the city [15].”

The case reveals three core values of media architecture as a service design tool.

First, the systemic intervention of touchpoint reconfiguration. The infrastructure is transformed into an editable interface through projection devices, constructing a superimposed experiential layer of physical space and digital content. This spatial programming strategy breaks the single transportation function setting and transforms the viaduct into a hybrid infrastructure for day and night time reuse. The Ephemeral Media Events created by the festival are essentially a dynamic test of the city’s service blueprint, verifying the feasibility of the time-sharing model through user participation.

Second, participatory service ecology construction. The artist team adopts a tactical urbanism strategy to activate the co-creative subjectivity of the citizens with minimal technological intervention (projection + walking path design). When viewers have to move their bodies to trigger the image narrative, they have essentially become co-designers of the service experience. This embodied interaction mechanism subverts the traditional media architecture’s viewer-viewed power relationship and establishes a service value network based on equal dialog.

Third, the elastic prying of policy levers. The project promotes institutional innovation through the creation of visible contradictions: the vibrant landscape formed by nighttime art activities contrasts sharply with the environmental damage caused by daytime automobile traffic. This mediated presentation of temporal and spatial juxtapositions enables policy makers to visualize the social benefits of infrastructure renovation, which ultimately leads to adaptive adjustments in municipal regulations. The media architecture here plays the role of a socio-technical prototype for policy experimentation, and its transient presence catalyzes the optimization of a permanent service system.

The concept of urban theater proposed by Sarsangi essentially points to the mediation object of media architecture as a service design [9] —it transforms the technical rationality of infrastructures into a perceptible, participatory, and iterative social process through the creation of contextualized meaning-producing arenas. This transformation mechanism provides a new paradigm for contemporary urban regeneration: through the strategic implantation of mediated service touchpoints, dysfunctional hard spaces are transformed into soft interfaces that cultivate civic identity.

2.2. Visualization of Environmental Data

“Yellow Dust” is a public infrastructure in the form of a 3D water vapor canopy that dynamically monitors, visualizes and partially remediates airborne particulate pollution through a variable cloud of yellow mist (Figure 2a). It uses DIY sensors and off-the-shelf building systems to transform abstract data on air quality into sensory experiences perceivable by the public, such as visual yellow mist and somato-sensory humidity regulation, while actively improving the local microclimate through humidification and cooling (Figure 2b). Unlike hidden traditional monitoring devices, the project discloses technical details in an open-source model, promoting air pollution management from a professional closed system to a collective participatory public practice.

2.4. Summary: Media Architecture Belongs to the Weapon against Top-Down Urban Services

This chapter analyzes three core values, three service design logics and three design perspective logics through the research and analysis of participatory architecture in media architecture. Whether media architecture constitutes a “weapon of confrontation” depends on its design goals and technical openness. If it is only used as a glorification tool for the government or capital, it is still an appendage of “top-down” power; however, if it gives citizens substantive control over the media interface and embeds However, if citizens are given substantial control over the media interface and embedded in a reflection on power structures, it may become a vehicle for bottom-up resistance. The politics of media architecture is always in a dynamic game, and its potential lies not in the technology itself, but in how it can reconfigure the distributional logic of urban power through design, policy and public participation.

The model can guide media architecture towards service design in real projects. In complex urban information service scenarios, it is necessary to integrate multiple information resources to provide citizens with one-stop access to services. The media architecture can be guided by the core value of “amplifying the voices of the marginalized” and conduct research and analysis on the information needs of different groups in the city through service design, with a special focus on the information access difficulties of disadvantaged groups and marginalized communities. According to the design logic, environmental data such as urban infrastructure data and public service facilities data are visualized and displayed on the platform with an intuitive interface to facilitate citizens’ understanding of the distribution of urban resources. From the perspective logic, a feedback channel for public participation is built so that citizens can participate in the decision—making process of urban services, such as making suggestions on the location and function setting of public service facilities.

However, media architecture’s role in future urban service design systems is not a unidirectional tool of innovation but always exists within the dynamic dialectics between technological rationality and social values. On one hand, it provides transformative potential by leveraging algorithmic empowerment, interactive interface reconfiguration, and distributed network construction—as evidenced by São Paulo artists converting façades into civic expression platforms through temporary projections, or Seoul’s “Yellow Dust” project redefining environmental governance through tactile perception. These practices validate its revolutionary value in enhancing decision transparency and activating marginalized voices. On the other hand, latent crises remain: when technology evolves into a new form of control mechanism (e.g., surveillance-oriented data visualization), it may reinforce spatial exploitation; unaddressed digital divides could solidify existing social exclusion patterns; overreliance on intermediation might erode the social attributes of physical spaces, leading to “screen democracy” replacing real public spheres.

Thus, the ultimate efficacy of media architecture hinges on balancing three dialectical relationships: symbiosis between technical instrumentality and humanistic values, adaptation of participation breadth to depth, and coordination between short-term innovation benefits and long-term institutional resilience. Only by integrating critical reflection mechanisms within service design frameworks—such as establishing algorithm audit systems to prevent black boxing, designing multimodal interfaces to ensure digital accessibility for vulnerable groups, and constructing elastic feedback systems to incorporate diverse interests—can we avoid its transformation into a new form of “spectacle society.” This dialectical perspective demands transcending technological determinism, acknowledging its transformative potential while maintaining vigilance against technological expansion boundaries, ensuring it serves the “human scale” rather than “data value.”

In summary, the application of this modeling framework in actual projects not only integrates multidisciplinary theories to provide comprehensive guidance and support for the project, but also creates a service experience with social value and innovation through the synergy of service design and media architecture. At the same time, its circular feedback mechanism ensures the sustainable development and continuous optimization of the project, providing a powerful tool and methodology for solving complex social problems and meeting people’s growing needs. In the future, with the continuous advancement of technology and the deepening of theory, this modeling framework is expected to play a greater role in more fields and projects, and to promote the development of society in a more fair, just and sustainable direction.

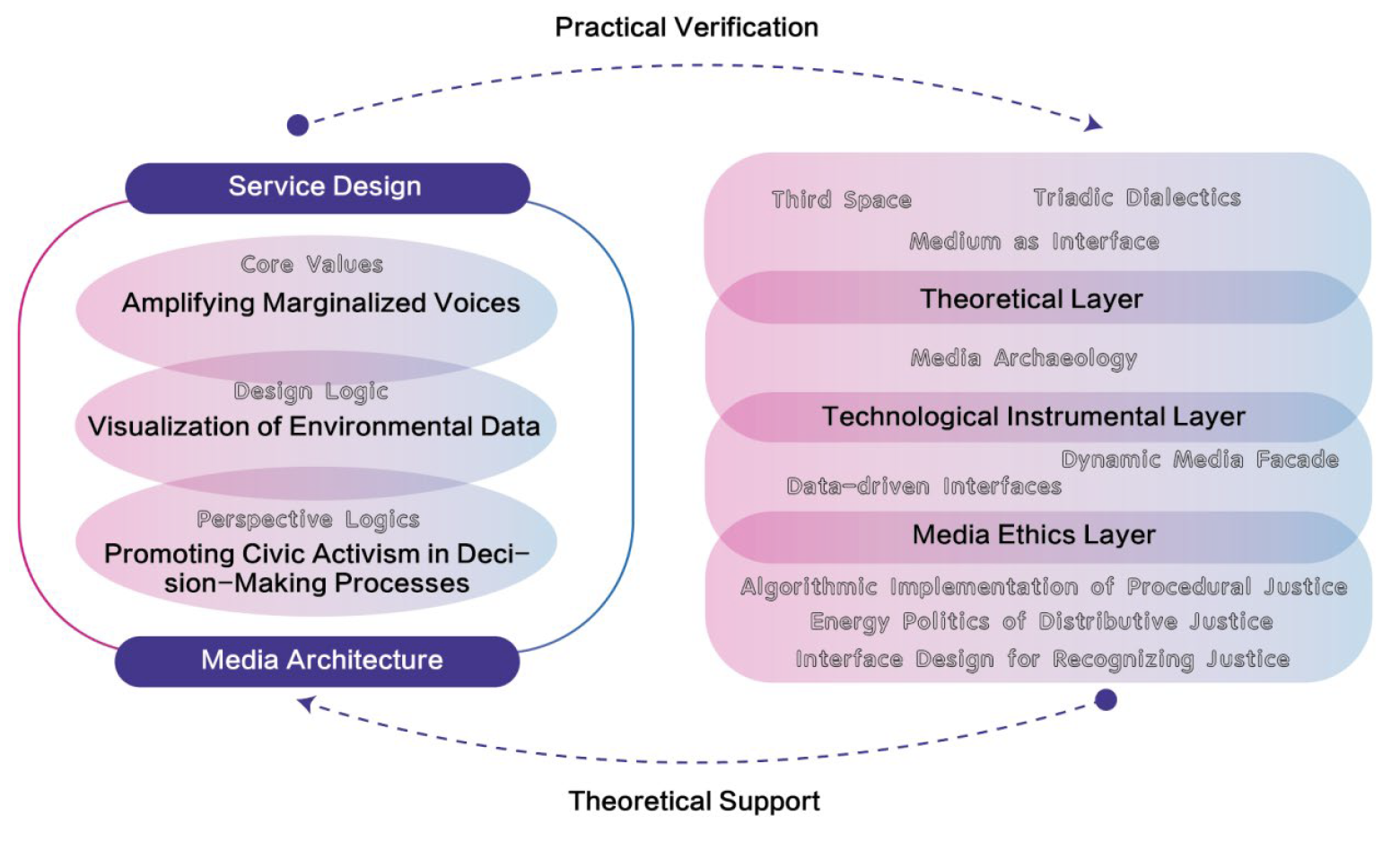

Conclusion: Coupling and Mapping of Media Architecture Service System

This study proposes a circular model framework with service design and media architecture as the core, supplemented by multidimensional theoretical support, aiming to build a comprehensive system that takes into account both technical practices and ethical values (Figure 4). The core practice part on the left side of the model consists of two major parts: service design and media architecture, with service design covering core values, design logic, and perspective logic; and media architecture interconnected with service design to form a two-way interaction. The theoretical support section on the right side is divided into three levels: theory layer, technical tools layer, and media ethics layer. The overall framework presents a cyclic structure, where theoretical support provides guidance for practice, and the results of practice feed back to theoretical improvement, and service design and media architecture realize innovation in interaction. The innovation of this model lies in the integration of multidisciplinary theories, which provides a systematic, dynamic and multidimensional perspective for service design and media architecture, and helps to realize the goals of social equity, civic participation and environmental sustainability.

1. Synergistic Paths of Confrontation between Media Architecture and Service Design

The chronic problems of contemporary urban planning are deeply rooted in the top-down power mechanism [6]. The complicity of capital and administrative power has given rise to homogenized urban landscapes, glass-walled forests have eaten up regional cultural genes in the name of modernity, and the disappearance of historic districts and the dilemma of a one-size-fits-all city reflect the aesthetics of power behind spatial production. This planning paradigm reduces citizens to passive recipients of spatial consumption, and the lack of public participation in the decision-making process leads to an imbalance in the allocation of resources—when urban renewal projects fall into a decade-long stalemate due to neglecting the demands of the indigenous people, and when performance projects create shocking ecological traumas, the traditional planning paradigm has been exposed as fundamentally flawed: it treats the city as an object that can be mechanically manipulated, and the city as an object that can be mechanically manipulated. The traditional planning model has revealed its fundamental flaw: it treats the city as an object that can be mechanically manipulated, but disregards the complexity of the city as an organic living organism and the mobility of the citizens as spatial subjects.

Media architecture refers to a form of architecture that combines digital media technology with architecture, and enhances the expressiveness and interactivity of the building through digital technology tools: such as LED displays, projection mapping, and interactive installations [7]. Media architecture not only focuses on the physical form of the building, but also on creating a richer, dynamic and interactive user experience through digital media technology. Media architecture makes urban space more interactive and dynamic through digital technological means, and through digital media technology, it can also display the city’s history and culture, artistic creativity and modern technology, and enhance the cultural connotation and image of the city. Applying media architecture technology on important nodes or landmark buildings in the city can enhance the city’s recognizability and attractiveness, and promote the city’s cultural exchange and tourism development. The interactivity and digital technology characteristics of media architecture provide a new way for the public to participate in urban planning. Through media architecture, the public can more intuitively understand the content and objectives of urban planning, and can also express their opinions and suggestions through interactive devices. This participatory mode of urban planning helps to improve the science and feasibility of planning [8].

Against this backdrop, media architecture reveals its revolutionary potential as a spatial critique tool in the digital age. This architectural paradigm transforms solid concrete into a fluid information interface through interactive LED façades, dynamic projections and intelligent sensing technologies. The OLED matrix of Berlin’s Climate Tower transforms abstract PM2.5 data into waves of light with gradient colors, upgrading the public’s ecological perception from rational cognition to embodied experience; and the photovoltaic façade of Singapore’s Marina Bay maps solar energy conversion efficiency in real time into a community energy quota, making the building’s skin a democratized interface for resource distribution. The essence of media architecture is to break through the physical boundaries of material space and reconfigure the power of spatial narratives through the hybrid field of interweaving the real and the imaginary—those marginal narratives that are obscured by the mainstream discourse are able to obtain a symbolic presence in the urban night sky. Service design provides methodological support for such spatial empowerment. It no longer sees architecture as a functional container, but as a physical carrier of a dynamic service system. The essence of this design thinking lies in the establishment of a recursive relationship of “space-service-subject”: the physical environment forms a closed loop of services through digital contacts, and the data of citizens’ daily behaviors regulate the spatial form to form an intelligent ecosystem with evolutionary ability.

Behind this technological integration is the deconstruction of the traditional power structure by service design thinking—when the skin of media architecture becomes a democratized display board of environmental data, and when the cell phone terminals of the residents are transformed into voting machines for spatial decision-making, urban planning is transformed from an elitist paper blueprint into a living process with the participation of all people. A subtle check and balance mechanism is established between the logic of capital and ecological responsibility. This spatial practice is rewriting the modernist urban narrative. It continues Jane Jacobs’ delicate observation of street life while realizing a contemporary translation of Henri Lefebvre’s theory of spatial production through digital technology. When Media Architecture materializes the methodology of service design into accessible spatial interfaces, architecture transcends the shackles of functionalism and becomes a political device for civic empowerment. In the future cityscape of blending reality and reality, every wall may become a sounding board for the expression of demands, and every street may be turned into a bulletin board for the distribution of resources, and this democratic practice permeating the daily space will eventually compose a more inclusive urban poem in the symphony of bricks and mortar and data.

While top-down urban planning has played an important role in urban development, its limitations are becoming increasingly evident. Media architecture and service design, through synergy, provide new ideas and methods to counter the limitations of top-down planning. Media architecture enhances the interactivity and public participation of urban spaces through digital technology means, while service design optimizes the process and quality of urban services by focusing on user experience and needs. The synergy between the two not only improves the science and effectiveness of urban planning, but also promotes the development of cities in a more open, inclusive and innovative direction.

Table of Contents

- Abstract

- Introduction

- Synergistic Paths of Confrontation between Media Architecture and Service Design

- Case Study of Media Architecture as Service Design

- Preliminary Construction of a Theory of Service Media Architecture

- Conclusion: Coupling and Mapping of Media Architecture Service System

- Author Contributions

- Funding

- Acknowledgments

- Conflicts of Interest

- Data Collection Description

- Author Biographies

- References

Abstract

This paper explores the intersection of sustainable design, environmental justice, and social innovation through the lens of media architecture and architectural media. As urbanization intensifies and climate crises escalate, design practices must evolve beyond technical solutions to address systemic inequities in resource distribution and ecological burdens. Focusing on the role of design as a service-oriented discipline, this research investigates how media architecture—a hybrid field integrating digital technologies, public space, and participatory engagement—can act as a catalyst for environmental justice. By analyzing case studies of media-driven installations and community-centric platforms, the study argues that architectural media, when embedded with principles of equity and sustainability, can amplify marginalized voices, visualize environmental data, and foster civic agency in decision-making processes.

The paper critiques conventional top-down approaches in urban design, advocating instead for co-creative frameworks that prioritize grassroots participation and socio-technical synergies. It examines how dynamic media façades, interactive urban screens, and data-driven spatial interfaces might democratize access to environmental information while challenging power structures that perpetuate spatial inequalities. Furthermore, the study proposes a theoretical model for “just transitions” in the built environment, where media architecture serves as both a communicative medium and a tool for systemic change, bridging gaps between policy, technology, and community needs.

By situating media architecture within the discourse of social innovation, this research contributes to redefining design’s ethical responsibility in an era of ecological precarity. It calls for interdisciplinary collaborations that reimagine public space as a site of environmental storytelling, collective action, and equitable resource stewardship, ultimately advancing a vision of sustainability rooted in justice and inclusivity.

Introduction

We stand at a paradigm shift in architectural practice, amidst the confluence of accelerated urbanization and digital metamorphosis. As buildings transcend their traditional materiality to become symbiotic interfaces between physical and virtual realms [1], architectural design confronts a fundamental redefinition of its role and functionality. In this hybrid future, the discipline faces three interlocking imperatives: innovating service ecosystems responsive to dynamic spatial demands, optimizing resource allocation through computational precision, and achieving ecological footprints commensurate with planetary boundaries. The central challenge confronting contemporary architects lies in orchestrating these transformations through design intelligence that simultaneously addresses anthropocentric needs and biocentric constraints—a balancing act where technological augmentation must harmonize with biophilic imperatives to redefine the architectural profession’s covenant with both human communities and the biosphere.

The concept of service design originated from the interdisciplinary intersection of management and marketing in the 1980s. In 1982, American scholar G. Lynn Shostack first introduced the term “service design” in her seminal paper “How to Design a Service,” emphasizing the systematic planning of service processes through design methodologies and pioneering the “service blueprint” tool to visualize intangible services [2]. While this theory sparked extensive discussions in management circles, service design only formally entered the design discipline’s purview in the 1990s. A pivotal development occurred in 1991 when Michael Erlhoff and Birgit Mager from the Köln International School of Design (KISD) incorporated service design into design education curricula, establishing it as an independent discipline. That same year, British scholar Bill Hollins’ monograph Total Design elevated service design from a management tool to a comprehensive design methodology [3].

The field achieved institutional recognition in 2004 when Birgit Mager founded the Service Design Network (SDN), the first global professional association dedicated to service design standardization. Subsequently, leading academic institutions such as Carnegie Mellon University and Politecnico di Milano established specialized service design programs, integrating it with industrial and interaction design domains. Contemporary service design employs systematic tools—including user journey maps and stakeholder maps—to optimize service processes while balancing user needs with provider efficiency. Its five foundational principles (user-centeredness, co-creation, sequentiality, tangibilization, and holism) have become cross-industry operational standards, shaping service innovation practices across sectors.

While service design and architecture belong to distinct disciplines, they share profound methodological and practical synergies, particularly under the dual influences of contemporary urbanization and digitization. Both fields prioritize user experience and systemic thinking [4]. Traditional architecture centers on functionality and aesthetics, whereas service design emphasizes user-centric systematic processes. However, driven by the experience economy, modern architecture has evolved from static physical forms into dynamic experiential platforms. Service design’s touchpoint theory is now applied to spatial design, integrating physical elements (e.g., lighting, materials) with augmented reality interfaces to craft emotionally resonant experiences.

The two disciplines also achieve methodological complementarity. Service design tools, such as user journey mapping, assist architects in analyzing interactions between users and spaces. Moreover, service design’s co-creation principle requires architects to incorporate diverse stakeholder needs — residents, governments, contractors — during planning phases, exemplified by collaborative workshops in community renewal projects.

In addressing urbanization challenges, their integration fosters synergistic innovation. Service design’s focus on optimizing systemic resource allocation aligns with architecture’s sustainability goals, reflecting shared commitments to ecological responsibility and equitable resource distribution in urban contexts [5]. Meanwhile, digitization—propelled by metaverse technologies—transforms buildings into hybrid interfaces blending physical and virtual interactions. Service design facilitates this shift by integrating digital touch points with physical spaces, redefining architecture as intelligent service agents rather than mere functional containers.

This convergence represents a paradigm shift from function-driven to experience-driven design. Service design equips architecture with methodological frameworks, while architecture provides service design with physical platforms for emotional expression. Their fusion not only addresses urbanization challenges —resource allocation, ecological pressures — but also redefines spatial value in the digital age: spaces transcend passive utility to become active participants in shaping social relationships and intelligent systems.

3.1.4. Media Archaeology Perspectives on Media Evolution

Media Archaeology Perspectives on Media Evolution Media archaeology perspectives reveal that the evolution of media from knotwork to LED façades is essentially an exponential increase in the visualization of spatial power. This evolutionary process demonstrates how media technology has gradually complicated the expression and control of spatial power to a finer and wider extent. In the context of media architecture, modern media technologies such as LED façade enable the visualization of spatial power through dynamic display and interaction, thus increasing the degree of visualization of spatial power. This improvement not only makes the expression of spatial power more intuitive and clearer, but also makes the control of spatial power more delicate and effective.

3.1.5. Summary: Tactile Democracy and the Breakdown of Sensory Hierarchy

This section uses the politics of the senses as a theoretical framework to reveal the revolutionary path of media architecture in reconfiguring the power structure of urban space through technological empowerment. Laura Marks’s theory of haptic democracy is concerned with breaking down the traditional hierarchy of the senses through the embodied cognition of interfacial touch, enabling marginalized groups to gain access to the discourse of spatial narratives [19]. In The Skin of the Film, Marks discusses the haptic dimension of the cinematic experience, emphasizing the important role of touch in perception and cognition [20]. Bennett’s hierarchy of the senses is a manifestation of visual centrism, which views vision as the highest or most superior sense and places the other senses in a lesser position [21]. Plato’s and Aristotle’s hierarchy of the senses not only established the tradition of visual centrism in Western philosophy, but also laid the basic framework for the formation of a visionary polity, especially with the flourishing of modern science after Kepler.

The “haptic democracy” created by the interactive urban screen breaks Bennett’s “sensory hierarchy” through the embodied cognition of interface touch, allowing marginalized groups to gain a voice in spatial narratives. While traditional urban spaces usually emphasize the senses of sight and sound, media architecture enables the usually neglected groups, such as the visually or auditorily impaired, to participate in and influence the urban narrative in a more comprehensive way through tactile interactions. This tactile democracy makes media architecture a new form of spatial democracy that changes the traditional power structure of spatial narratives by enabling marginalized groups to participate in the narrative of urban space through tactile interaction. This change not only makes urban space more inclusive and pluralistic, but also makes the narrative of urban space richer and more complex.